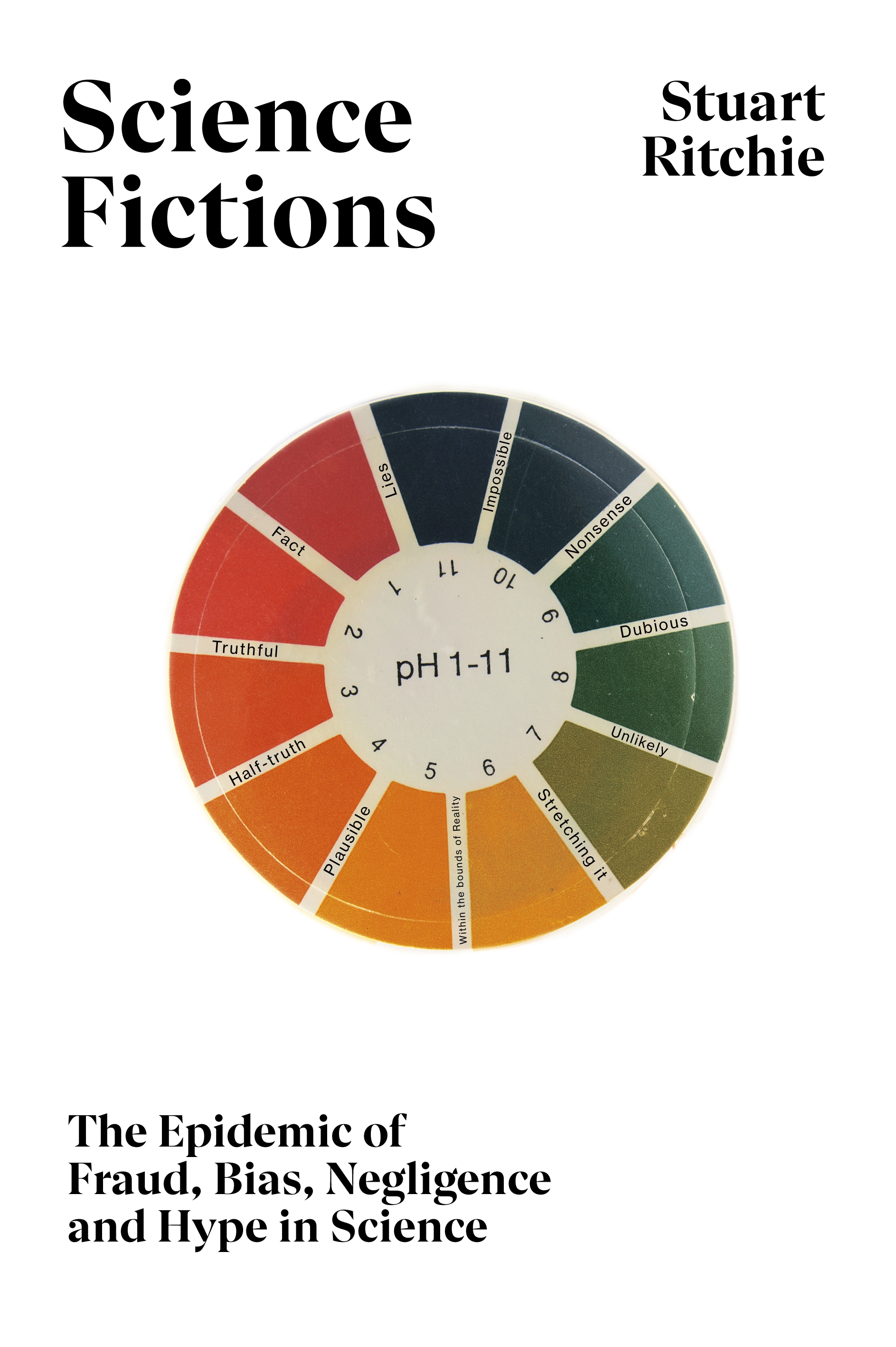

Science Fictions - The Epidemic of Fraud, Bias, Negligence and Hype in Science

Science is often held up as the gold standard for discovering truth. But what if the system itself is rigged in subtle, structural ways? Stuart Ritchie’s Science Fictions shines a spotlight on the hidden biases and perverse incentives that distort scientific research.

The Problem with What Gets Published

One of the central issues Ritchie tackles is publication bias. Simply put, studies that don’t find an effect often end up unpublished, left in researchers’ proverbial desk drawers. This becomes a real problem when meta-analyses—studies of studies—attempt to determine the average effect of a treatment or intervention. If only positive results are considered, the average effect will be misleadingly inflated.

Another culprit is p-hacking, a statistical sleight-of-hand that involves running many analyses and only reporting the ones that yield significant results. Because journals typically only publish findings with p-values under 0.05—a convention arbitrarily set nearly a century ago—researchers are incentivized to keep slicing and dicing the data until they find something “significant.” The result? A literature flooded with false positives.

Incentives That Reward Quantity Over Quality

Why do researchers p-hack or slice their papers into thinner and thinner pieces (“salami-slicing”)? Because the system rewards it. Academic success often depends not on the quality of your research, but on how many papers you publish and in which journals. In some countries, like China, there are even cash bonuses for publications in elite journals like Nature and Science. The result is a flood of incremental, sometimes redundant papers that bloat CVs but offer little scientific advancement.

Pharmaceutical companies have exploited this too. By publishing multiple papers based on the same trial, they create the illusion of broad evidence for a drug’s effectiveness—knowing that busy doctors rarely have the time to scrutinize the details.

At the root of this is a lack of research funding. Scientists must compete for limited resources, and those with the longest CVs often win. It becomes a vicious cycle: the more you publish, the more money you get, and the easier it is to publish more.

Toward a More Honest Science

Ritchie doesn’t just diagnose the problems—he offers paths forward.

-

Fraud Detection Software: Automated tools can catch statistical inconsistencies or anomalies, flagging potential fraud or simple human error. Automated reporting tools can also mitigate the human error, which is common when reporting results in a paper.

-

Independent Data Collection and Analysis: Separating those who collect the data from those who analyze it could reduce confirmation bias.

-

The Multiverse Approach: Instead of cherry-picking analyses, researchers could report all reasonable variations and aggregate them, giving a fuller picture of their findings.

-

Open Data and Code: Sharing data sets, analysis scripts, and methods increases transparency and allows others to validate or critique findings.

5 Rewarding the Process, Not Just the Results: Grant funders and institutions should recognize the value of data collection, replication efforts, and methodological rigor—not just flashy results.

A Personal Reflection

Reading Science Fictions as a PhD student, it’s hard not to feel conflicted. You learn what needs to change, but you also learn what it takes to survive in academia. The system subtly pushes you toward the very behaviors the book criticizes—because that’s how careers are built. Even with tenure, you’re still tied to grant cycles, departmental politics, and students who are navigating the same pressures.

Maybe real scientific freedom only comes at the end of a career—when there’s finally nothing left to prove.